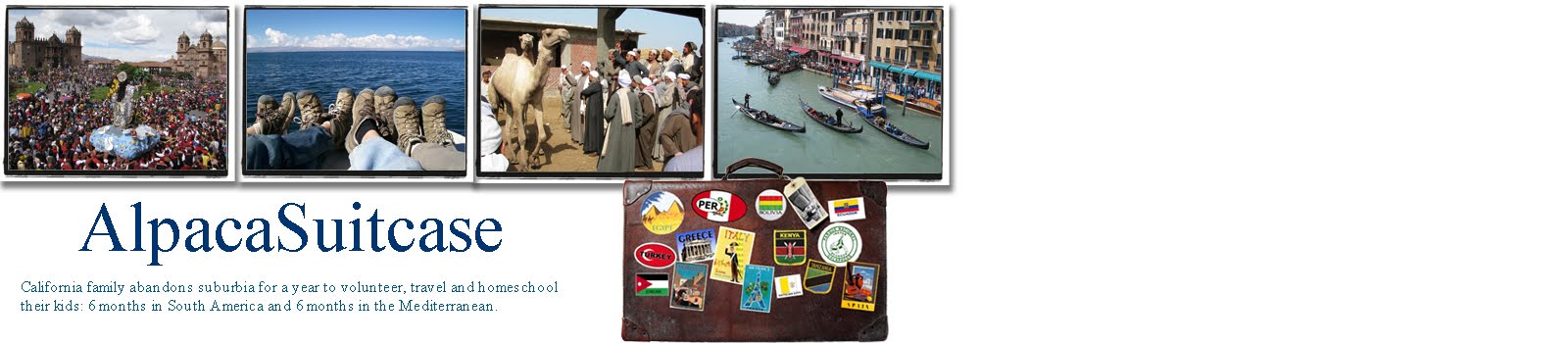

I’d love to take full credit for getting our kids onto the Cusco Swim Team but the truth is I subcontracted most of the job to company in Mountain View, California. Yes, I’m talking about Google.

|

| Piscina Municpal in Cusco, Peru |

Frustrated with my results, I loaded Google Earth onto my work computer and started systematically scanning the satellite photos of Cusco, Ayacucho and Arequipa – the three towns that we were targeting. While virtually soaring above the Cusco city center one afternoon, I spotted a light-blue, opaque rectangle not far from a train station. Was that a pool? Was that an indoor pool?

I quickly typed in the name of the street and district into the Google search bar along with “piscina” and “natación”. The results quickly came up and displayed a news article and accompanying video newscast about what was indeed a pool. As I slowly read the article and watched the video, I was struck by simultaneous feelings of horror and elation: horror as I read about 17 kids rushed to the hospital for inhaling excessive amounts of chlorine and elation as the newscast showed clips of a beautiful, indoor heated pool in the middle of the Andes. I justified the chlorine accident as something that could happen anywhere and gave in to the elation of finding a pool. More searching failed to turn up a swim team of any kind, however. I decided to check out the pool during my planned Peru visit in February 2009.

By February, we had narrowed our sights on Cusco and I went there for 10 days to set things up for our family. In addition to checking out Spanish schools, jobs and housing, I thought I’d take a look at the pool I’d found. On my second afternoon in Cusco, I went there and asked if there was a swim team and the woman working there gave me a definitive “no”. On the third day, I returned in the morning and a different woman told me there was a “Swimming Academy” and that I should come back at 2:00 pm in the afternoon. At 2:00 pm I talked to yet another woman who said the Swimming Academy meets early in the mornings and that I should return the next morning at 7:00 am.

Thinking that by now I should probably give up, I walked over at 7:00 am the next morning and asked again. This time, the same woman told me to wait while she brought over the coach, whose name was Cristian. I told Cristian what I was looking for and he seemed mildly interested. In colloquial and rapid-fire Spanish, he talked about practice times, swim meets and the twice-yearly TransAndean Youth Games. He asked the kids’ ages and when we would be back in Cusco and we exchanged email addresses.

In my numerous Spanish-language conversations while setting us up in Cusco, I’ve sometimes had exchanges like this that have gone nowhere. I’ve found that if people have something to gain from an interchange (i.e, shopkeeper, innkeeper, tour guide) the motivation and politeness displayed in the initial face-to-face conversation is more likely to be sustained when following up via email or telephone. With Cristian, I just didn’t know if he felt he had something to gain by our relationship.

With this in mind, I sent him an email with some apprehension once I returned home. I sent an email that clearly detailed information about us as well as the many questions we had. I decided to send the kids’ best times from the previous season to hopefully add some incentive.